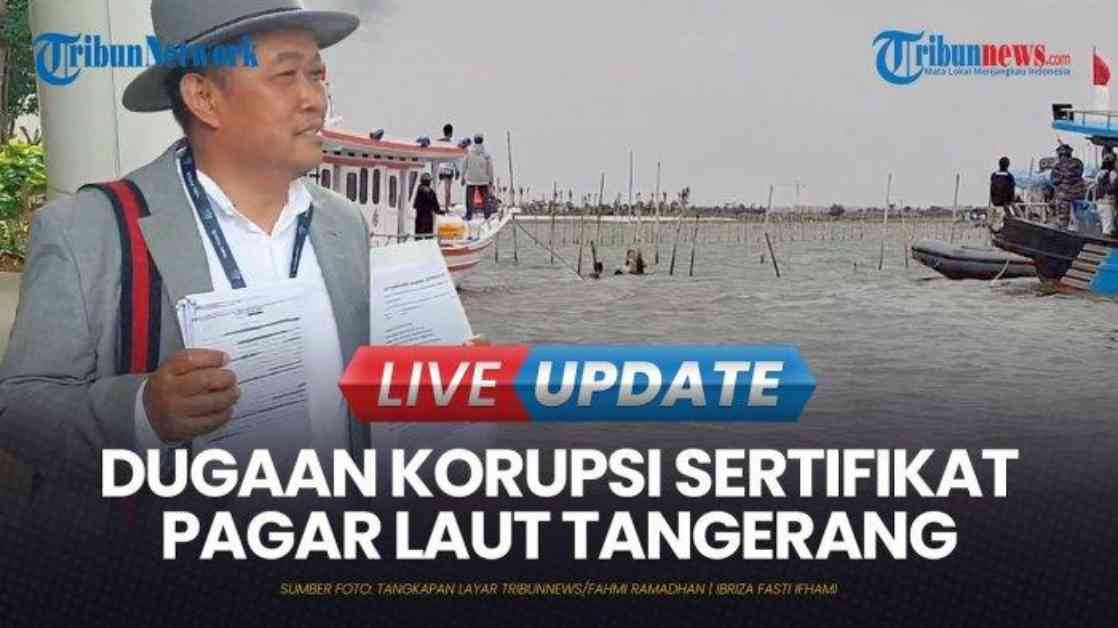

In a stunning turn of events, the veil of secrecy surrounding the ownership of the sea fence in Tangerang has finally been lifted. The bamboo sea fence, stretching a whopping 30.16 kilometers from the shores of Tanjung Pasir Village in Teluk Naga District, Banten, to the coasts of Kronjo Village in Kronjo District, Tangerang, has been at the center of a corruption scandal that has rocked the community.

The Indonesia Anti-Corruption Society (MAKI) has taken matters into their own hands, reporting suspicions of corruption in the issuance of Building Use Rights Certificates (HGB) and Land Ownership Certificates (SHM) related to the construction of this sea fence to the Attorney General’s Office (Kejagung) of the Republic of Indonesia on Thursday, January 30, 2025.

The coordinator of MAKI, Boyamin Saiman, revealed that the reported parties to Kejagung range from village officials to officials at the National Land Agency (BPN) of Tangerang District. The sea fence, currently being dismantled by the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (KKP) and the Indonesian Navy (TNI AL), was found to possess HGB and SHM certificates issued since 2023 by the Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning (ATR).

According to Nusron Wahid, the Minister of ATR and Head of BPN, there are a total of 263 plots of land in the form of SHGB, with 234 plots under the name of PT Intan Agung Makmur, 20 plots under PT Cahaya Inti Sentosa, and 9 plots under individuals. Additionally, there are 17 SHM certificates issued in the Tangerang sea fence area. These certificates, totaling 263, are located outside the coastline, essentially floating above the sea.

Nusron emphasized that the existence of areas beyond the coastline renders some plots of land ineligible for certification and prohibits them from being private property. He also pointed out that the issuance of certificates for the Tangerang sea fence was riddled with procedural and material flaws.

In light of these revelations, MAKI has reported several village officials from Kohod, Pakuaji, and officials from three other districts—Tronjo, Tanjung Kait, and Pulau Cangkir—to Kejagung. Boyamin alleges that they violated Article 9 of the Anti-Corruption Law on forgery of administrative books or special registers. The certificates issued in 2023, according to Boyamin, are counterfeit.

As the investigation unfolds, questions loom over the legitimacy of land ownership in Tangerang and the implications of the alleged corruption on the community. The intricate web of deceit and malpractice surrounding the issuance of certificates for the sea fence has cast a shadow of doubt over the integrity of local officials and the land titling process in Indonesia.

The residents of Tangerang are left to grapple with the uncertainty and the realization that the sea fence they once thought protected their coasts could be at the center of a scandal that undermines their trust in the system.

The unfolding saga of the Tangerang sea fence serves as a cautionary tale, underscoring the importance of transparency, accountability, and ethical governance in safeguarding public resources and upholding the rule of law. As the investigation progresses, one thing remains clear: the truth behind the sea fence in Tangerang is far more complex and murky than meets the eye.